For more than forty years of archaeological research and writing, I have been obsessed by two dates: 9600 BC and 6350 BC. Both were left to us by ancient Greek historians, who have received small thanks since both dates are traditionally dismissed as “mythic” by conventional archaeologists on the grounds that the people of those epochs would have had no way of recording time. But astronomers have very recently discovered that the night sky itself might well have served as a means of measuring and recording time as far back as the Paleolithic age.

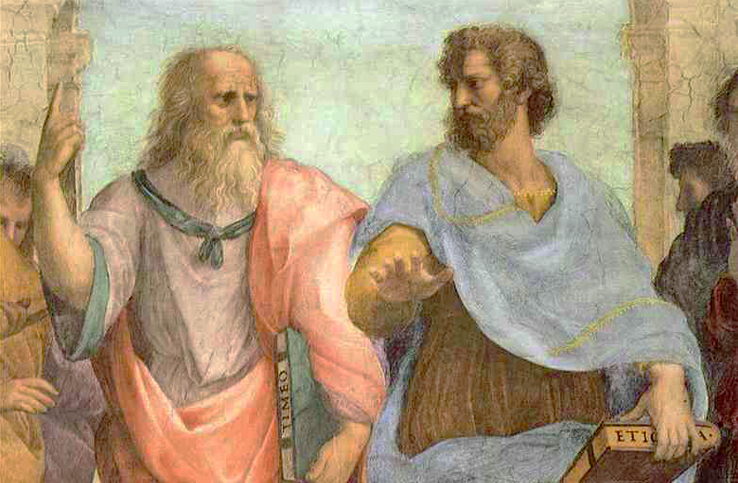

Perhaps we should have had more faith in the impeccable reputations of our Greek sources. With regard to the c. 9600 BC date, Plato tells us that the story told to Solon by an old Egyptian priest in the Timaeus and Critias dialogues – the story of the catastrophic destruction of Mediterranean lands that had occurred “9,000 years ago” – was described by Socrates himself as “true history.” (Solon, a Greek statesman, is known to have visited Egypt in 600 BC, giving us the date of c. 9600 BC for the disaster described by the priest.)

The second date, c. 6350 BC or thereabouts, was said by several different Greek historians, using different contexts, to mark the birth of the Iranian prophet Zarathustra. Both Aristotle and Eudoxus are among those who apparently believed that Zarathustra lived “6,000 years before the death of Plato” (350 BC), thus c. 6350 BC.

My efforts over the years to give the Greek historians a fair hearing based on modern archaeology have produced three books, Plato Prehistorian: 10,000 to 5,000 BC in Myth, Religion and Archaeology (Rotenberg Press, 1986), When Zarathustra Spoke (Mazda Publishers, 2005), and most recently The Bear, the Bull, and the Child of Light (2019), a prehistoric novel with footnotes! The reason for the footnotes – and for that matter the novel itself – is that recent discoveries by the wider scientific community have greatly improved the chances that what the Greeks said was true.

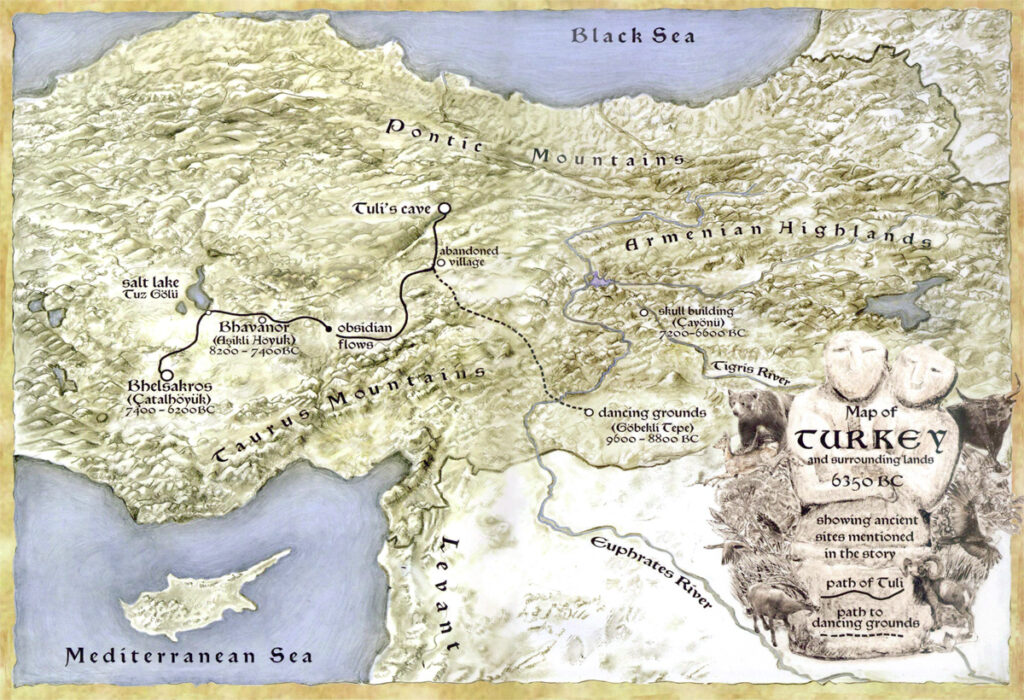

I have mentioned the current research into the likelihood that Paleolithic people used the night sky to record time. Of particular importance in this work is the newly excavated site of Göbekli Tepe in southeastern Turkey, dated c. 9600 – 8800 BC. Using data from the Greenland ice cores, scientists have discovered that the founding of Göbekli Tepe coincides with the end of the last of the ice ages (the Younger Dryas, c. 9600 BC), which was marked by an unusually sudden and inexplicable warming. The monumental stone pillars of the initial level at Göbekli Tepe were carved with a myriad of animal forms and theorized to be an ancient zodiacal recording of the moment of a particular event – perhaps associated with the end of the Younger Dryas – that was of critical importance to those who built the site. Was it the same cataclysmic event as the one dated by Plato’s Egyptian priest to c. 9600 BC?

As for the second of the dates in question, c. 6350 BC, which several Greek historians claimed as the birth of the Iranian prophet Zarathustra, evolutionary biologists have recently traced the long-sought origin of the Indo-European languages back to central Turkey between c. 7500 and c. 6000 BC. This span of time almost precisely coincides with the dating and placement of the site of Çatalhöyük, an improbable settlement of some 8,000 people on the Konya plain of central Turkey.

The Indo-European language would have then spread from Turkey both east (eventually becoming Indian and Iranian) and west (becoming most of the European tongues) along with the profusion of new farming villages that arose in both directions. As Zarathustra’s missionary-borne message was strongly oriented toward the cultivation of the earth, this massive spread of farming in the years following the c. 6350 BC date given by the Greeks for his birth must surely strengthen their claim.

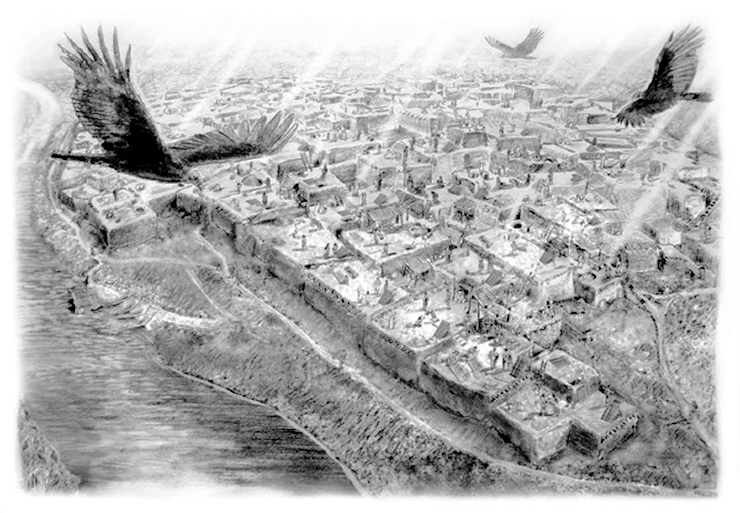

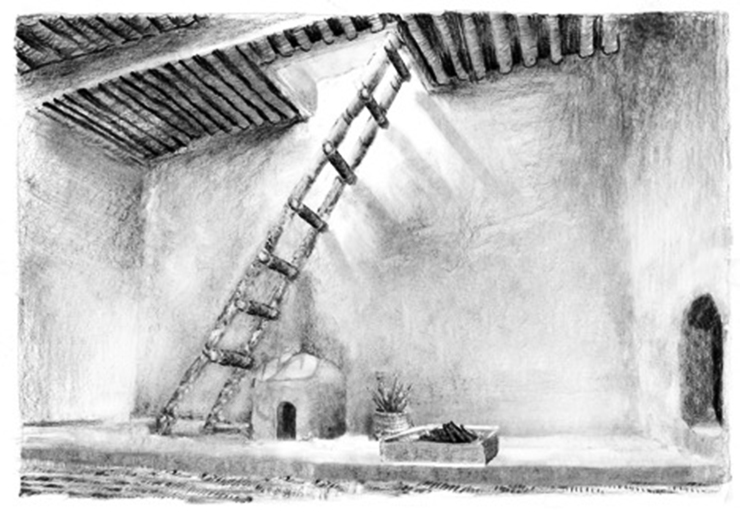

These new perspectives on the two dates which have fascinated me for so long ultimately inspired the writing of the aforementioned prehistoric novel with footnotes. The story is actually a memoir, told in the first person by an old man, Tulirane (Tuli), who had been born around 6300 BC into a family of hunter-foragers living in northern Turkey. By that time the stone pillars at Göbekli Tepe in southeastern Turkey (c. 9600-8800 BC) had long since been covered over, leaving a low hill that served as sacred dancing grounds for the hunters of the region at the summer solstice. On his way to this sacred ground with his family, Tuli is captured, enslaved, and taken by an obsidian trader to Çatalhöyük (“Bhelsakros” in our story). We then follow him into the agglomerated chambers of this enormous site, rooms that open only to the sky with little or no contact with the earth.

Tuli is ultimately rescued by the disciples of a Prophet who, like Zarathustra, sought to renew the earth through the care and cultivation of all her kingdoms. As described in the novel’s Epilogue, the number of new farming communities which then sprang up in lands to the east and west of Çatalhöyük suggests that his mission was successful.